|

PROPOSED SOLUTIONS 1. National Primary Day Under this plan, all states would hold their primary or caucus on the same day-a pre-election Election Day. The idea was introduced as early as 1913 by Woodrow Wilson but has gained little momentum. For all intents and purposes, as front-loading increases as a trend, the nation seems to be naturally moving in the direction of what amounts to a national primary. "You had 20 states in February in '96. You had 35 states in February 2000. I predict you will have 39 states in February 2004," said Sansonetti. "So, it is shifting to what is basically a national primary. It is a de facto national primary right now."18 This plan would almost certainly increase salience and turnout in primaries and caucuses. More Americans would believe that they had a say in choosing the candidates for president. However, it would almost certainly minimize direct contact between candidates and voters. Campaigns would be waged on the national level, primarily through paid and free media, making it virtually impossible for candidates without personal fortune or establishment backing to compete. Depending upon the specifics of implementation (such as whether independents and swing-voters would be allowed to participate) a national primary day could keep party nominees more in line with mainstream views. Success in such a contest would provide strong evidence of electability. Party rank and file, and perhaps independent voters, would be able to exert their undiluted preferences on presidential nominees, an unsettling prospect for the party elites. Such a distribution of power could hamper the formation of core party platforms-often the hallmark of viable presidential candidates. Understandably, the parties are reluctant to discuss this sort of plan, partly because it would diffuse control over the selection of their nominee, undermining the exclusive and predictable hierarchy of conventions. An event of this magnitude would also render the conventions even more of a non-event than they are today. The last serious dialogue addressing a national presidential primary was silenced in 1970 by the Democrats' Commission of Party Structure and Delegate Selection. 2. The The Delaware Plan is the brainchild of Delaware GOP state chairman Basil Battaglia. Under the Delaware Plan, the states would be grouped into four "pods" according to population, as determined by the decennial census. The smallest thirteen states would go first, followed by the next smallest thirteen states, then the twelve medium-sized states and finally the twelve largest states. Small states like The plan passed the Republican National Committee Rules Committee in early

2000 but failed at the July 2000 Republican Convention in The Delaware Plan boasts several advantages and addresses the problem of front-loading. Battaglia and other proponents defend the plan as the logical way to encourage voter participation and discourage front-loading, while giving small states an opportunity to play an important role in the process. Letting the smallest states begin the contest, "allows a grassroots campaign to catch fire. The Jimmy Carter example in '76, the Gary Hart example from'84, the Eugene McCarthy example for that matter in 1968," said Sansonetti.19 This plan can help lesser known and under-funded candidates gain momentum from victories in the smaller "pods." This will also diminish, although not eliminate, the benefits of homesteading years in advance, since seven or eight states will head the pack instead of just one. A CBSNews.com article notes that "Plan backers say it will preserve

the 'retail' side of politics, keeping candidates down on the ground talking

to people where they live and work, not just up on the airwaves through

expensive television ads."20 It could extend the direct

attention of grassroots campaigning enjoyed by citizens of Having several small states in which to mount grassroots campaigns gives more candidates a chance to post a win in the first pod. However, having thirteen small, geographically separate states in the first grouping makes it very difficult to wage a sizeable effort in every state. This may force candidates to choose a few markets deemed more viable, leaving other states out in the cold. The Delaware Plan aims to lengthen the process, giving voters a chance to observe and follow the candidates through a period of three or four months instead of a quick five or six weeks. Plan supporters argue that candidates will have a chance to prove their mettle because only 9 percent of all delegates (in the GOP plan) would be chosen in the first round. This means it is likely that the eventual winner would not be decided until the later rounds, maybe even in the final round, which determines 50.5 percent of convention delegates, according to Sansonetti.21 Opponents argue that money will still play too large a role in the selection of a nominee for president. Even the first rounds, with relatively small states spread across the nation, may prove expensive. Candidates will have to last longer in the race, from a five- or six-week scrimmage to a three- or four-month marathon; therefore, the key to staying in the race is money. However, an extended race could help lesser-funded candidates by giving them time to build on any momentum they can muster in the small states. Often candidates drop out despite voter interest and a good early showing in the polls because there was simply not enough time to fundraise and organize for later contests. The Delaware Plan may address this time-crunch problem. Delaware Plan proponents argue that instead of just one winner, there

could be multiple winners in the Plan's first contests. Because a win in One of the main problems with the Delaware Plan is that it might create

four mini-national campaigns. Each grouping of states is spread out across

the country, making it very difficult to have a concentrated effort anywhere.

This plan would likely increase the wear and tear on candidates or the media.

Moreover, having more than one or two small states at the beginning of the

schedule would force candidates to choose among the group for more viable

markets and opt to disregard others. Thus, candidates would probably end up

saturating the other states with television ads and direct mailings to

compensate for the lack of personal appearances. It is already very expensive

waging a media campaign in the two major media markets reaching New

Hampshire-Manchester and This plan may also favor East Coast states as a result of the news cycle.

"If you have a choice between 3. Rotating Primary Plan The National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS), comprising of

chief election officials across the nation, believes the nominating system

today is unworkable and is pushing to scrap the front-loaded primary

calendar. In 2000, the NASS recommended the Rotating Presidential Primary

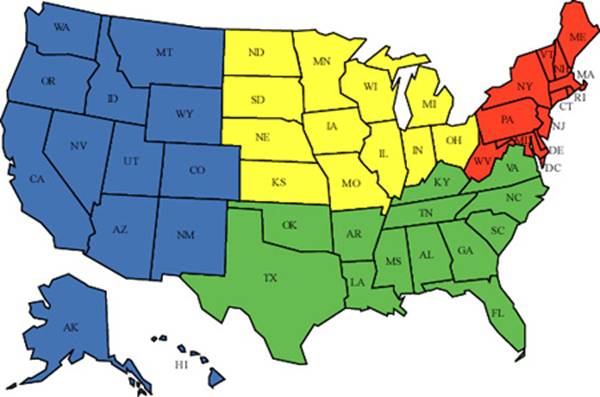

Plan and suggested that it be in place before the 2004 primaries.23 Under the proposal, the Proposed Regional Nomination Map

Primaries to select national convention delegates would be grouped by

region: Eastern states will hold their primaries in March, the South in

April, the "Front-loading the presidential primary process is forcing candidates to begin campaigning earlier than ever," said Secretary of State Joyce Hazeltine, former president of NASS and South Dakota Secretary of State. "By implementing the rotating regional primary plan, we can more clearly define the presidential campaign season and provide voters and candidates with the opportunity to focus more intently on candidates as they discuss issues relevant to each region."24 The Rotating Presidential Primary Plan shares some of the advantages of the Delaware Plan. Like the Delaware Plan, this regional plan also aims to extend the race and eliminate frontloading, therefore allowing voters the chance to observe candidates in a longer period of time and giving dark-horse candidates some opportunity to build upon momentum. This plan also addresses some of the weaknesses in the Delaware Plan.

Candidates can conduct regional campaigns, which allows

them to concentrate on regional issues and possibly save money by focusing

their media buys. This ability to camp out would likely reduce wear and tear

on the candidates, the staff, and the media, and promote meaningful

interaction between candidates and voters. Candidates will be exposed more

than ever before to the concerns and complaints of regional voters. They will

hear about the no-tax pledge in One issue not addressed by the Rotating Presidential Primary Plan is the propensity of candidates to homestead. For starters, this plan fails to break up the Iowa-New Hampshire monopoly. As a result, these two states will continue to set the tone for the entire race, and the candidates will continue to camp out in these states, preserving the permanent campaign. Homesteading may actually become more prevalent under such a plan. Because campaigns will know decades in advance which region will go first in any given election year, they may choose to spend even more time pandering to voters in an entire region. This predictability will likely dictate the timing of presidential bids by certain candidates, as they await a year in which the regional order benefits them. It may actually extend homesteading over several election cycles, rather than just years. 4. Regional Lottery System During the Symposium, Center director

Larry Sabato proposed the Regional Lottery System.

This plan divides the An American Election Lottery determines the order in which the four regions will participate in the process. Run by a five-member nonpartisan part-time election lottery commission appointed by an organization such as the National Association of Secretaries of State, the new lottery could become the Powerball of politics. On a predetermined date approximately six months prior to the first contest (so as to allow the regions ample time to prepare for an election) a lottery with four colored balls representing the four regions on the color-coded primary map will be drawn, with the first region drawn going first and so on down the line. Because it is a state-based system, each state will have the right to choose between a primary election and a caucus. To encourage the caucus system, which is cheaper to organize and assists in party-building, Sabato proposes that caucus states be first out of the gate-on the first of the month, followed by primaries on the fifteenth. The Regional Lottery System also enjoys many of the same advantages as the Rotating Presidential Primary Plan, but the key to this plan is the lottery used to determine the order each region will participate in the nominating process. Because candidates are unable to know more than a few months in advance which region will lead off the calendar, homesteading is eliminated and candidates are forced to focus equally on all areas. The lottery plan also contributes to the development of a primary campaign that retains its competitiveness while pushing the campaign itself closer to the national convention to sustain voter interest throughout the process. The lottery could also insert a degree of excitement into the nominating process. Over the long term, it gives more states, based upon the law of averages, the opportunity to be one of the first contests and have a substantial impact in candidate selection. The nomination calendar kicks off in March and continues until June under this plan, giving the voters and candidates breathing room and reversing the trend toward front-loaded contests. "The American people might like it. It might reduce costs. It certainly would reduce wear and tear. It makes more sense to most people. It encourages focus on regional issues. And it certainly shortens the permanent campaign," argued Sabato.26 While Sabato's plan does address some flaws of the NASS plan, it does not deal with the fact that regional events may approach the scope of a national campaign and force an over-reliance on the media to communicate with the public. The four regions are still very large areas, which would likely favor candidates with a large amount of money or outstanding name recognition at the very beginning of the campaign. Also, because candidates will not know until very late which region will go first, they may be forced to begin national campaigns years in advance. REFORM RECOMMENDATIONS The Center advocates Sabato's Regional Lottery System, but with a few significant twists. First, the Center does not believe that the comparative advantages of caucuses or primaries warrant creating a scheduling incentive favoring one over the other. The parties and states should determine their own priorities in this regard. Secondly, the Center wishes to enhance Sabato's

original proposal with an addition suggested by Craig Smith during the

Symposium. Smith recommended creating a second lottery to pick two small

states to begin the contest, as The Challenge of Change As a general point, the Center calls upon the parties and the states to work together in seeking solutions to the diminishing involvement of voters in the nominating process. The Center believes parties and states should bear much of the responsibility in utilizing the nominating process to encourage and promote voter participation in the political process. It is our hope that the discussions of the Symposium and this report serve to encourage this sort of leadership. Given the difference of opinion between large and small states, plus the unpredictability of population shifts, dividing the map into regions suitable for all states will be a daunting task. Moreover, trying to effect change in all fifty states will be challenging. This requires coordinating party policy with state laws, both of which tend to become mired in political jockeying. States will have mixed reactions to any reform proposals. Large and small

states have conflicting interests that will most likely cause gridlock in any

reform action. The Republican and Democratic parties are also hesitant to enact drastic change. Any reform effort will require cooperation between the parties. One party is unlikely to move without the other, for fear of creating a strategic disadvantage for its candidate. Furthermore, the parties have to balance competing objectives: the interests of the party and the interest of the general public. Parties only wield influence and power when their candidates are elected. They do not get anything for a good effort. Therefore it is not necessarily in the interest of the party to extend the nominating process. However, the burden of increasing accessibility to the process and encouraging voter participation has more and more fallen on the shoulders of the parties. Energizing voters through party-sponsored activities and mobilizing voters to the polls are inevitably in the interest of the parties. This would allow parties to create stronger bases and wider support. Yet, it is questionable whether parties will bare the opportunity costs of extending the nominating process. This directly translates into giving up some control of the party's nominee. But for the good of the republic, parties should take a step back and re-examine their role in promoting the health of our democracy. _______________ Notes 1. Ben White, "After Drama Left the Primaries, Voter Turnout Fell Dramatically," The Washington Post, September 1, 2000, p. A5. 2. Bob Smith, "Fairness in Primaries," memorandum to the Republican National Committee members and delegates. June 2000. http://gwis2.circ.gwu.edu/. 3. Jill Lawrence, remarks to the 4. Lamar Alexander, remarks to the 5. Michael Dukakis, remarks to the 6. Craig Smith, remarks to the 7. Data on 8. Terry M. Neal, "Primaries Could Be Decisive by

Mid-March," The 9. Kathleen Kendall, "Communication Patterns in

Presidential Primaries 1912-2000: Knowing the Rules of the Game,"

research paper for the 10. Vaughn Ververs, remarks to

the 12. Richard A. Ryan, "Early Primaries are Leaving Big States in Also-Ran Position," detnews.com, May 10, 2000. http://detnews.com/2000/politics/0005/10/a13-53312.htm. 16. Thomas E. Patterson, "Public Involvement and the 2000 Nominating Campaign: Implications for Electoral Reform," The Vanishing Voter Project, April 27, 2000. http://www.vanishingvoter.org/releases/04-27-00prim-4.shtml. 17. Tom Sansonetti, remarks to

the 20. Susan Walsh, "Primary Reform Clears GOP Hurdle," CBSNews.com. July 26, 2000. http://www.cbsnews.com/now/story/0,1597,219401-412,00.shtml. 23. For more information, see http://www.nass.org/issues.html#primaryplan. 24. South Dakota Secretary of State Press Release. "State Election Officials Call on Governors, State Legislators, and Political Parties to Work Together on Proposal on Inject order into Primary Process," July 28, 1999. http://www.state.sd.us/sos/releases/regional_presidential_primaries_.htm. 25. Larry J. Sabato, remarks to

the 27. States with seven or less electoral votes: Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming. 28. South Dakota Secretary of State Press Release. July 28, 1999. |

|

|

|

|